– To best use international cyber capacity building we should understand its trajectory and where it might go next.

For more than two decades, cyber-related knowledge and equipment has been shared across borders under the umbrella of international cyber capacity building. It has benefitted, and benefited from, a wide range of participants from police to professors, civil servants to civil society, seasoned incident responders to schoolchildren learning to surf the web. These projects provide a variety of support – including advice, training, services, software, equipment and more – to help countries protect themselves and their citizens in the digital age.

There are now more than 250 international cyber capacity building projects running each year, involving over 650 organisations. Almost every nation has participated in some way: providing or receiving assistance or often both.

Yet, despite its reach, this new field of international cooperation remains relatively under-researched, leaving important questions about its origins, evolution and future unanswered. This article points towards some of those answers, drawing upon insights in a new report commissioned by the European Union into trends and scenarios in cyber capacity building.

Growth

There are many stories to tell about cyber capacity building, but ours starts with its growth. Data from the Cybil Portal – an online repository of projects – suggests that, while the first activity started earlier, the number of projects active each year has been growing since the late 2000s. We can chart this trend and overlay projections of what would happen if it continued at its current pace or slowed.

Number of active international cyber capacity building projects (data: Cybil Portal, 2021)

The growth of cyber capacity building can also be seen in the increasingly complex network of organisations involved with projects. These organisations might be governments, their agencies, companies, universities, international bodies, civil society or regional bodies. By looking at the projects that were active each year we can map a network of organisations involved in capacity building (nodes) and the projects that connect them (lines). What we find is a growing and increasingly complex network of organisations that, as we might expect, mirrors the growth in the number of projects. As not all projects have been added to the Cybil Portal yet, we know this is a partial picture and the full network will be even larger.

Cyber capacity building actor network (data: Cybil Portal, 2021)

Parent communities

When we trace this growth in projects and participation to its roots we find the field of international cyber capacity building was formed by the coming together of different parent communities.

Each parent community has its own culture, aims and path into the field. There is also a wide difference in the extent to which each is integrated into a core cyber capacity building community, participating in the forums and processes through which this core community comes together.

Coordination

With so many organisations involved in cyber capacity building, coordination is essential. Without it, projects duplicate each other’s work or leave gaps that a better coordinated approach could fill. There are good examples in cyber capacity building, but many practitioners feel the field’s rising aspirations for good coordination are not being implemented consistently or fast enough.

Maturity

Better project coordination is one sign of a field’s maturity, but not the only one. Our research found several indicators of a gradual, but not yet universal, professionalisation of programming in cyber capacity building. For example, capacity building programme teams are expanding, hiring specialist staff and improving project design. Much of the professionalisation we saw applied good practices and lessons learned from the parent communities, especially international development.

Future scenarios

So where does the field go next? To project where cyber capacity building might head in the future, we should first consider the backdrop of global megatrends. Organisations tasked with studying the future warn the world is likely to experience increasing global competition as power shifts away from states and Southward and Eastward. The spread of the fourth industrial will bring the benefits of growth and personal opportunity, but also the disbenefits of more powerful and easily accessed tools for causing cyber harm and the social challenges of automation and surveillance. The pace of change in our school, work and personal lives will remain rapid in ways that are empowering for some and a cause of concern for others.

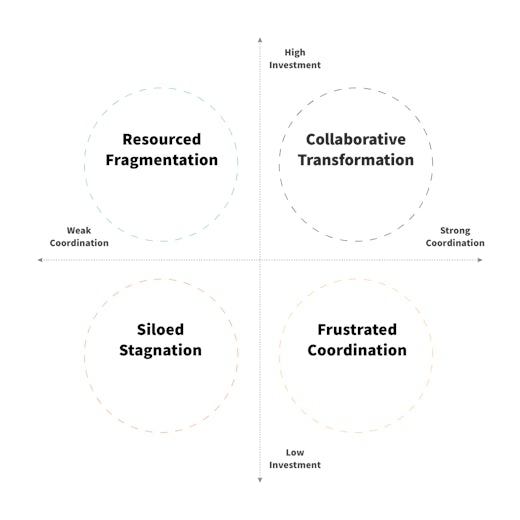

Cyber capacity builders can do little to change the backdrop of global megatrends. However, closer to home, the trends in their own field are both of immediate relevance and easier to influence. To explore potential future scenarios we can see what might happen if two of the most important trends – growth and coordination – took different directions. In one direction we can imagine a positive trajectory for the trend. In the other we can play out what would happen if the trend stalled or went into decline. The interaction between the two trends and the two directions for each produces four possible future worlds.

In the EUISS report you can read about these four worlds, which I and co-author Nayia Barmpaliou call Siloed Stagnation, Resourced Fragmentation, Frustrated Coordination and Collaborative Transformation. The interactive infographic below contains a short insight into what might happen in each scenario.

Using the report

Whatever your interest in cyber capacity building we hope you will find something in the report that is of interest and use. It contains information on how practitioners are approaching common challenges, opportunities and decisions. It provides a high level and long term view that can be difficult to see when immersed in daily operational work or coming to cyber capacity building for the first time. Its approach to exploring future scenarios provides a framework that can be adapted, or used as it is, to inform strategic planning at the programme or organisation level. And it contains concrete recommendations for all involved in the field.

Cyber capacity building could be an effective enabler of digital benefits for nations and of better international cooperation. Or it could be a small footnote in the history of why countries fell behind and fell out with one another in the fourth industrial revolution. Those working in the field do not have the power to guarantee which path we take, but their decisions do have the power to influence it.